EDEN AND EGYPT

This week, in synagogues around the world, we are deep into reading from Exodus, the second book of the Torah, Shemot, as we call it in modern Hebrew, or Shemos, as it’s called in those parts of town where cholent is usually served for lunch on Shabbos.

What a magnificent narrative this book contains. It is replete with most of the elements of great drama – pathos and anger, injustice and poetic justice, divine calls and close calls, adventure and misadventure, heroes and heroines, bad guys and good guys, chapter after chapter about the building of a new worship center - the Mishkan or Tabernacle in the Sinai, a moral code that has transcended the ages, divine worship and false worship, miracles and mayhem, and of course an introduction to one of history’s most unique personality portrayals – the prophet Moses who with Gd’s help ultimately brings about the redemption of an entire people from slavery.

Every time I read this book, or indeed any of the five books, I am reminded that part of the genius of Torah is its parallelisms, and not just those within each book, but also those between the books. You see, the beginning of the Book of Exodus is parallel in many ways to the beginning of the Book of Genesis.

Genesis begins with the birth of the human race, Exodus begins with the rebirth of the Jewish people.

Genesis begins with a prohibition to eat the fruit of two trees; Exodus begins with a prohibition against Hebrew baby boys.

In the first few chapters of Genesis, Noah builds an ark to save all living things; in the earliest part of Exodus, an basket ark (the same Hebrew word) is built to save Moses who then saves the Jewish people.

Early on in Genesis, Adam and Eve are expelled from Eden and an angel with a burning sword stands at its entrance to prevent their return; while early on in Shemot Moses encounters a burning bush as prelude to the Jews ultimately leaving Egypt ... led by a pillar of fire that prevents the swords of Pharaoh from forcing them to return.

The parallels go on and on, even down to lists of begats – so and so is the descendant of these and they are the ancestors of them – not the most exciting chapters in either book, but ultimately instructive in determining the ancient peoples that were extant in the world of about 3000 years ago, as well as a record of how we trace our descent from earliest days. Eden and Egypt are also parallel, though opposites, as I’ll explain in just a moment.

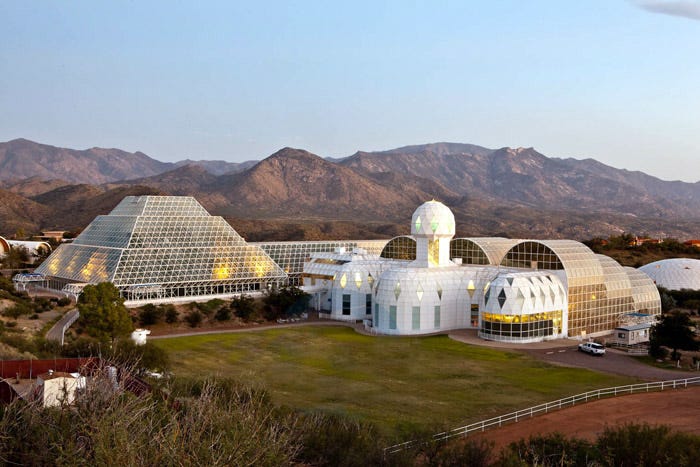

Biosphere II

Do you by chance remember the well-publicized and much written about experiment attempted in the Fall of 1992 in a desert location named Oracle, Arizona, some 60 miles northeast of Tucson? It was both interesting and instructive. Four men and four women, ranging in ages from 27 to 67, took up residence in a 3.15 acre compound known as Biosphere II.

This glass and steel geodesic dome complex, the original design of which was created by Buckminster Fuller, was the size of three football fields, and contained a variety of atmospheric areas – five in all:

a rain forest with waterfall;

an oceanic area complete with breezes, waves, and coral reef;

a savannah – grassland;

a marshland area;

and a desert environment.

Biosphere II also contained a working farm and, of course, a modern habitat to house its human inhabitants.

This self-contained mini-world had some 3,800 plant and animal species from which the eight people who were selected to live in it drew food and with which they shared water, air, and waste recycling. Intended to be totally self-sufficient, the only outside influence allowed was a supply of natural gas to power an electric generator. The eight humans lived in relative luxury with phones and FAX machines, computers, TVs, VCRs, exercise equipment, and a communications control center that connected them with the outside world. But once they moved in, the space was sealed and no one else was allowed to enter.

I enjoyed reading about the rules and regulations for Biosphere. The eight dome-dwellers could visit any of the five climate zones at any time – it was only a two minute walk from one to the other; they could pluck fresh fruit off of any of the trees or bushes – banana, papaya, citrus, etc.; they could engage in forming any sort of inter-personal relationship with one another, even intimacy was permissible; they could enjoy one cup of coffee a week made from beans grown inside the dome (there was even goat's milk for those who didn't take it black); they could drink wine if they could figure out how to make it from any of the pesticide-free plants or fruits inside the dome. In short, there was a lot they were permitted.

However, there were several things not allowed – they couldn't call for food from the local take-out, because nothing from the outside was allowed in; the women were not allowed to get pregnant, because of the medical complications caused thereby, and because of ethical considerations of bringing a newborn into an experimental setting. Because of waste disposal concerns, bidets and sponges replaced all paper products; and, finally, no one was allowed to leave during the two-year experiment unless they were seriously hurt, very ill, or ... having a nervous breakdown.

Biosphere though sealed soon became awash with accusations of improprieties. The project sponsors pumped in outside fresh air and installed a machine to scrub carbon dioxide from inside the dome, and they acknowledged that the dome had been pre-stocked with a food supply. They also admitted that a crew member who left for medical treatment returned with a bag full of supplies. There are those who argued that such tinkering was just so much fine-tuning on this first-of-a-kind venture. Others maintained that these outside supplies invalidated the whole thing and made Biosphere II just another exercise in close proximity living.

Somehow, I found the accounts of Biosphere most compelling, especially back in the early 1990s, long before the international space station. Just imagine a mini-planet with everything in it, and everything in it within immediate reach by everyone in it. It reminded me immediately of two other such self-contained environments. Both of them were also experiments in living. One we call Gan Ayden - a garden east of Eden and the other we call Mitzrayim - the land of Egypt.

Eden

First of all, one might say that Biosphere is reminiscent of the Garden of Eden experience – four Adams and four Eves reliving Genesis. Eden is indeed an interesting construct. The story is as well known as any in literature, and it is focal to at least two great religions – Christianity and Judaism. (Islam claims these first two as Muslims, but doesn’t make much else of the story.) Yet even more fascinating is the fact that while both Judaism and Christianity share the very same story, we don’t view it theologically in the same way.

Christianity has interpreted the Garden as the scene of human failure – site of the sin or fall of Adam and Eve. For the Church, eating of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil became synonymous with sexuality, which, in turn, was seen as being counter to Gd's wishes. Hence, for the Church, Adam and Eve, and by extension all future generations, fell from grace and were cast out of the Garden as punishment. No one can re-experience Eden or, metaphorically, heaven except through what the Church has come to define as the core of their belief system – salvation through faith.

Jews have never seen the story in that way. To us, by eating of the Tree of Knowledge, Adam and Eve became fully aware of their creative potential and, therefore, fully human. Humankind was not chased from Eden as punishment for sin, indeed, there was no sin in awareness, nor was there such a thing as the fall of humankind, because as far as Judaism is concerned, sexuality is normative to the human condition and not sinful except when it betrays trust. As my invented Yiddish saying goes, “Gd gave us the plumbing ... and we shouldn’t use it? Vat kind Gd ve got here?

Adam and Eve were driven out of the Garden so that they would not also eat of the Tree of Life and thus become immortal.

In the Jewish frame of reference, the Garden of Eden is not a real place; Torah sets it amidst four rivers that don’t intersect, and the garden itself is not in a place called Eden, but rather in a place east of Eden. Therefore, Eden – the Hebrew word means pleasure, is a metaphor for a good beginning. Life we see as being good, and each person born into this world enters pure without stigma of any kind. Jews do not believe in original sin. We enter this life as blessed and full of potential. So Eden is a metaphor for childhood, or, at least, every childhood should be Eden – nurturing, plentiful, beautiful, carefree, lovely, with every need – food and clothing and shelter, provided and within reach. Childhood should be Eden-like, a time/place with little care or concern … along with a smattering of socializing regulations – don’t eat this, don’t touch those, don’t say or do that, clear the dishes, feed the chickens, and go help your grandmother. Childhood, like Eden, is reflective of innocence, and, Eden, like childhood, is a limiting experience – don’t eat from those two trees.

Eden to the Jew is a theological, metaphoric fantasy land – a place where Gd "walks (?!) in the Garden toward the cool of day"; a place in which Gd lets Adam name the animals and fashions Eve out of a rib. In Eden, a snake talks. There is childhood and perhaps a hint of adolescence in Eden, but, there is no sense of adulthood there. In the Garden, life is without human guile, without want or strife or conflict. Hence, it takes a snake (real or proverbial) to introduce the subtlety of choice to these first very naïve, naked youngsters.

But Eden is (gasp) not perfect! You see, no worship takes place in Eden ... and no conception or birth, and no growth, and no human creativity either. Eden is innocence and naivety without want. It’s an arcade without the need of coins; Disneyland without a credit card.

Adam and Eve have to leave Eden not as punishment, but simply because to stay there would, ironically, have been a dead end. They had to leave Eden in order to become fully human – in order to work for a living, in order to exercise choices, in order to feel pain and joy, and in order to give birth to Cain and Abel and to Seth. It is outside of Eden that senses develop, emotions are exhibited, and awareness begins. It is only outside of Eden that worship (in the form of sacrifices) is possible let alone necessary, it also outside of Eden that death becomes part of the equation of life. Thus, from a Jewish perspective, it is only outside of Eden that life becomes real – that life can have any meaning at all.

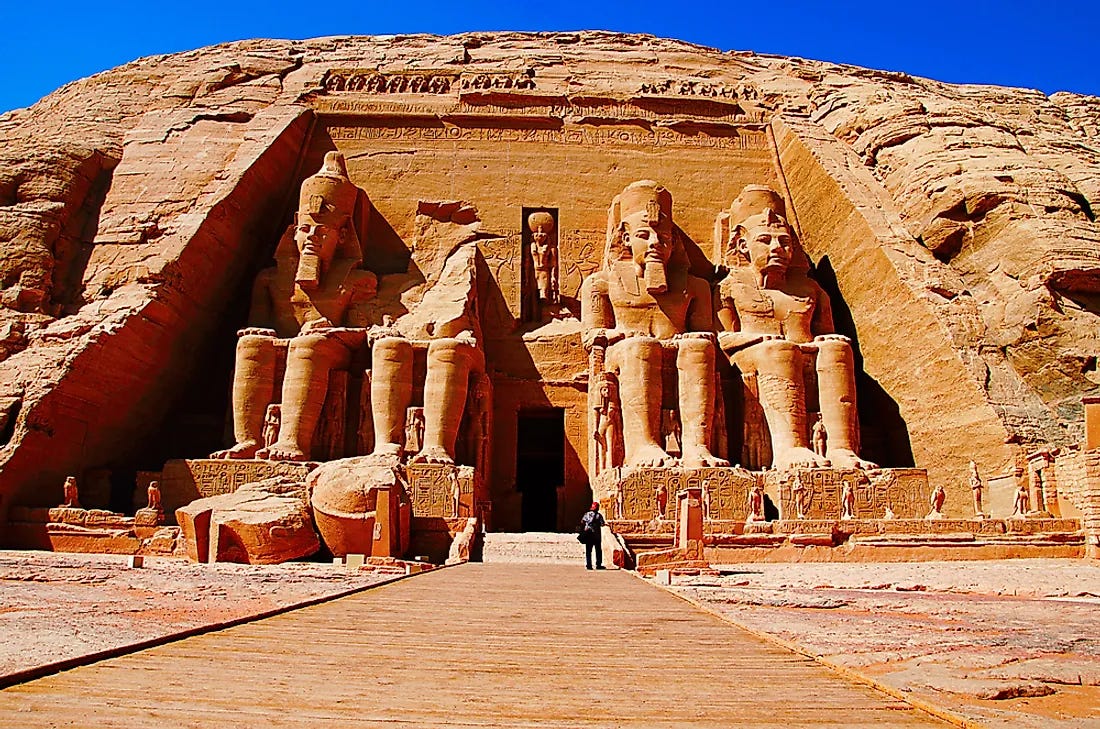

Egypt

Now Egypt is also a self-contained biblical environment. Metaphorically, to the Jewish mind-set, Egypt is the flip side of Eden. If Eden is destination, the place one wants to find again, wants to return to, Egypt is depot, the place one is ready to leave. But more than that, Egypt is enslavement and denial and fear and confusion. The Hebrew word for Egypt - mitzrayim, means constriction, enclosure, narrowness of mind and spirit. Egypt is Pharaoh, all-powerful human conqueror, abusive and controlling. In modern times, Egypt is wherever being a Jew is dangerous.

• Eden is play without work; Egypt is work without play.

• Eden is recreation without procreation; Egypt is procreation without recreation.

• In Eden there is only childhood; in Egypt there is only adulthood – children and childhood are destroyed.

Interesting isn't it that no worship takes place in Egypt, either. Moses comes to Pharaoh at first to obtain release for the Jewish people ... so that they may go three days into the desert in order to worship Gd. In the biblical paradigm, Egypt is where ... there can be no human fulfillment.

If it is Gd who must drive Adam and Eve from Eden lest they stay and live on and on as non-creative children, it is Gd through the efforts of Moses who must also drag the Hebrews out of Egypt lest they become the non-creative robots of a dehumanizing, totalitarian system.

So Eden and Egypt become paradigms for places one must leave, places that are not good, not conducive to human growth and development. In modern terms, I sometimes think of Eden as a sort of neglectful orphanage for children, while I see Egypt as the equivalent of an abusive work or family environment. I’m glad I never experienced either.

From Eden, Adam and Eve go to some unnamed, unspecified area – let's call it "the great outside." Time does not exist in Eden, the entire story takes place on day six of creation. Therefore, history only begins in the great outside. That is also where Cain poses the first moral question, "Am I my brother's keeper?"

From Egypt the Israelites (let me clarify – in Egypt we are Hebrews, once out of Egypt we are Israelites) ... from Egypt the Israelites go into a great outside – the Sinai Desert. An empty wilderness? A worthless, barren place? Oh, no, to the contrary. In the biblical account, the desert is metaphor for life itself. Three of the five books of Torah takes place in that desert. On a mountain peak in the midst of that someplace, Moses receives or perhaps conceives civil, criminal, and moral law. There amidst the dust and the rocks, men and women wrestle with theology – can we worship a Gd we cannot see, or can we believe in a calf mask made of gold by our own hands? In the heat of the everyday, the Israelites fight against enemies of flesh and blood, as well as against their own personal doubts and fears.

A hunger for food, a thirst for power, and a quest for purpose and for justice plague them continuously. Moses, who redeemed them from one oppression, works ever more subtle miracles to meet the persistent challenges – water comes from rocks, food in the form of quail comes from the skies, and manna just appears ... unfailingly from the morning dew on bushes.

Though free, some of the people now in the desert want to return to Egypt. Slavery or not, they remembered melons and leeks and onions and fish in abundance, and they remembered that in slavery there are no decisions to make, no choices to have to work through. “Take care of our simplest needs,” they seem to be willing to say, “and we will turn over our bodies and souls.” That is always a deadly exchange. Torah metaphor insists that life is a desert in which we wrestle with our needs, our desires, and the strength of our personal integrity – our character. We are not meant to live in paradise nor are we meant to live under the thumb of a despot.

And unlike Eden or Egypt where there is no future only an eternal present, time does exist in the Sinai Desert – 40 years pass by, an entire generation.

And in the Sinai a dream of the people sustains – a dream that says that tomorrow will see us in a better world, tomorrow in the Land of Promise, tomorrow Israel, tomorrow a world in which all are indeed our brother's keeper, in which all shall love neighbor as self and shall care for the poor and the stranger because we were strangers in the Land of Egypt.

Only in the turmoil of the real world, outside of Eden and outside of Egypt is life really lived. Only in the deserts do we build our communities and our Tabernacles and ... our cemeteries. Only outside of fantasy land, only where we are vulnerable can we create and grow and dream ... even if, ironically, that dream is for a sort of Eden once again.

Indeed, the metaphors of Egypt and Eden seem to be teaching that our task is to be independent and not enslaved, to be fully human – neither childish nor divine, to be of the real world and fully in it. Our life challenge is to work out relationships with Gd as well as with each other. Dreams of a new Eden, a new promised land, may motive our efforts, but to live with all the dignity we can muster is our only mission.

And so, that Biosphere experiment failed, not because some fresh air or some supplies were let in from the outside. It was doomed from the start because it isolated human beings. Purporting to be a new Eden, it was also very much a new Egypt – a fancy prison – a place where new life was prohibited and from which leaving was not allowed. At a tad over three acres, regardless of the variety of environments, it was still a narrow place. A place that fosters the status quo is debilitating. A place without exit is dehumanizing.

In the earliest chapters of Shemot, Moses asked what Gd’s name is, and Gd declares: “Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh – I Shall Be What I Will Be.” As if to say that God evolves. What a fantastic thought that is. Indeed, as we grow and we evolve, HaShem (kiviyachol - as it were) evolves too. God exists wherever we build, wherever we struggle – Gd exists in the deserts of life ... and not so immediately in the Edens or in the Egypts ... and, most likely, not in a Biosphere whose purpose was to create space without motion, place without time, people without problems, a world without birth, adults without childhood, and a mini-Genesis without purpose or an ennobling dream. Certainly, that was not what Gd intended when Moses was sent to free the people, nor was it in the final analysis what Gd intended with a garden planted east of Eden.

Nor would I imagine what Gd intended for any of us – for without challenges, without direction, without moving forward there is only existence – Eden or Egypt, and that is not life.

May we all have enough sense to put our dreams of Eden and our dread of Egypt behind us ... and strive to continue onward – kadimah, move purposely forward.

Thank you for your creativity and compelling drash on Eden and Egypt!

ישר כח